A literary short story inspired by Virginia Woolf

Author’s Note

The seed for “John Hates Lemons” came to me during a Jensen McRae concert. I went not for myself, but because a friend I love suggested her music, and I wanted to share in that joy, even if I couldn’t feel it the same way. I’ve always hated love songs—perhaps because they remind me that romantic love feels distant to me, if not entirely unreachable. I wanted, so badly, to relate to the heartbreaks, the golden beginnings, and the swell of emotion that makes people cry quietly in the dark. But I couldn’t. I’ve never loved someone for years. Not in that way. But John has. John is a character I created some time ago, loosely inspired by the generational conflict in Alan Bennett’s The History Boys—men shaped by war, tradition, and contradiction. John is a veteran. He lives with his wife. He says things like “men these days are soft” and refuses to call himself sentimental, but he brings his wife’s banana bread to the queer couple next door and watches the game with them, grinning. John hates many things—lemons, abstract art, politics at the dinner table—but he does not hate his wife. He thinks most poetry is nonsense, but not the poems she paints in brushstrokes across their hallway wall. In some ways, I think John is what I imagine love might look like after the noise quiets. A kind of steady, worn-in devotion. A man who hates lemons, but eats the pie anyway.

John Hates Lemons

John hates lemons.

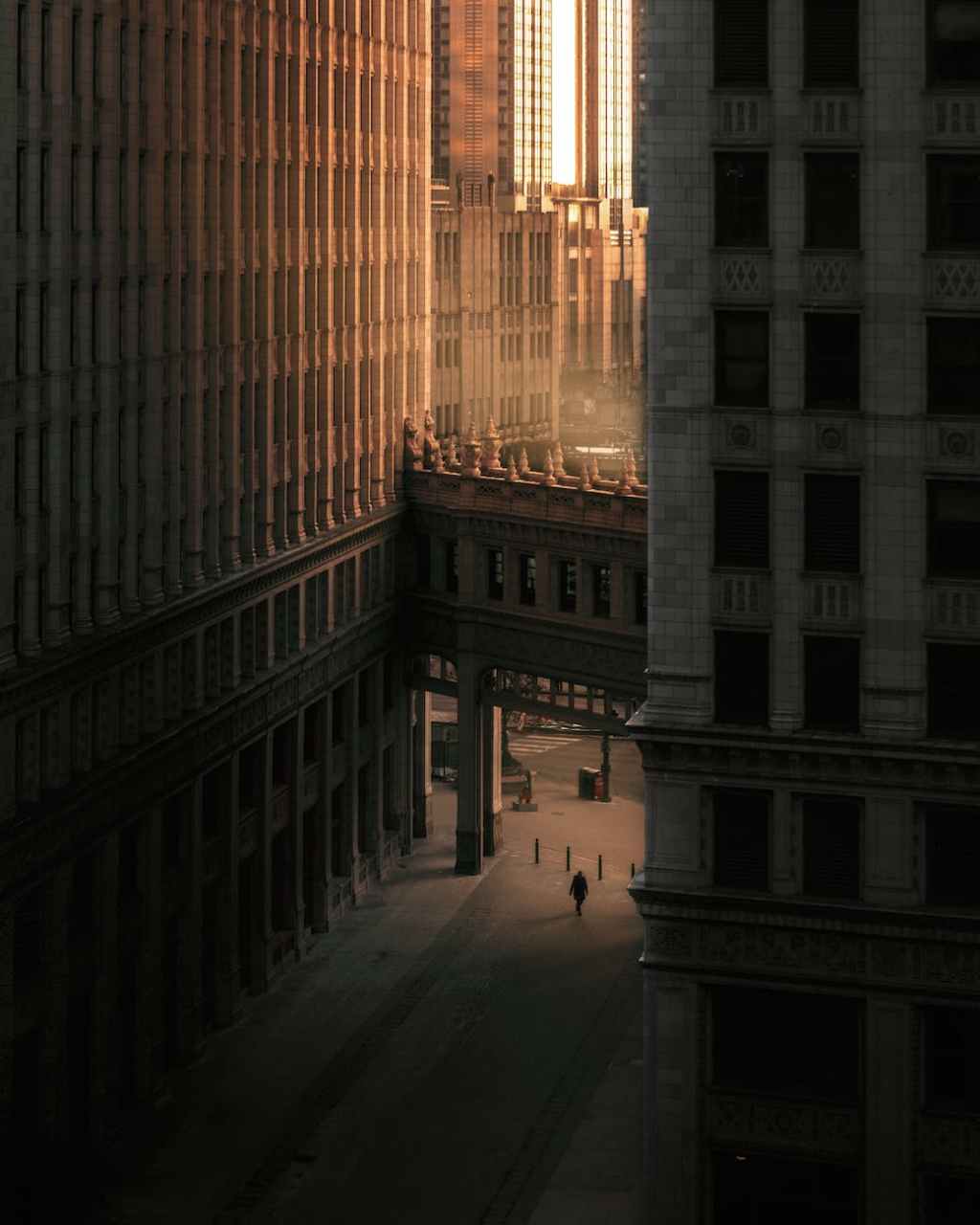

He always has. He hated the citrus sting before he ever knew it had a name. Said it curdled his milk, and John is a man who still drinks milk with his supper—white, obedient, unchanged. He pours it too fast, as if hurrying through a ritual he no longer believes in. I watch the bubbles gather at the rim of his glass like children leaning over a well, curious about the dark.

When he was a boy, he threw a lemon at another boy who called him “foreign.” The irony, John says now, is that the boy’s name was Giovanni. But names only betray their accents in the mouths of others.

We’ve been married for fifty-three years—fifty-four, if you count the year he left. And I always do.

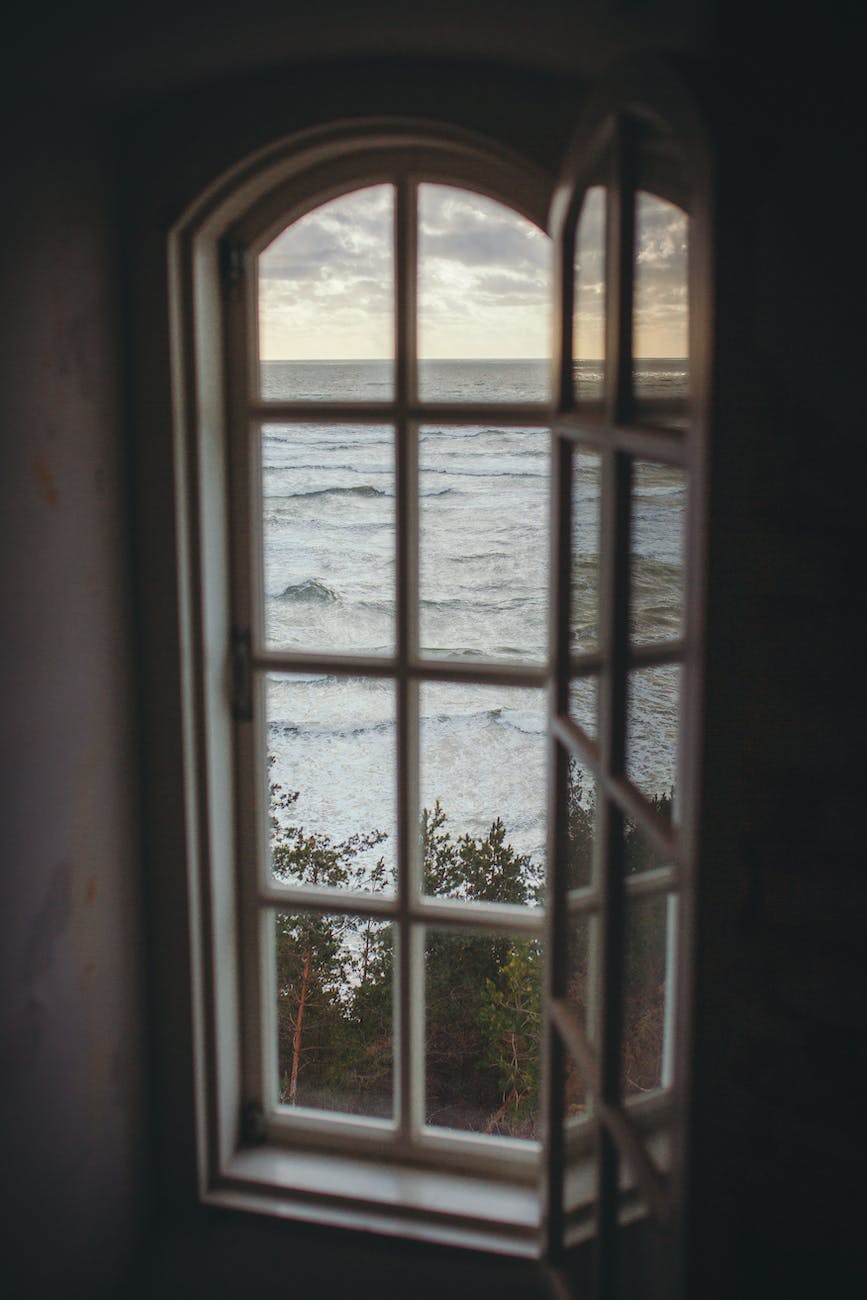

Now, in the blue-tiled kitchen where we take our meals—John with his milk, I with my silence—a single lemon rests on the windowsill. It arrived in a box of government vegetables. A mistake, perhaps. Or a gift. Its skin is yellow as bruised light, and how it glows against the pane reminds me of a wound trying to heal. I find myself looking at it longer than I should, longer than is necessary. I think of sunlight filtered through curtains, and how he once stood in that exact patch of light with his collar askew, so ordinary it hurt to look at him. How many mornings have I watched him sit like this, hunched over his glass, as though drinking were a duty. It used to annoy me- the slowness, the slurping, the way he’d blink at nothing for whole minutes—but now I think I was always watching for something else. Some signal. Some crack. Some tenderness he might have offered if he’d only known how. I suppose there’s a kind of love in watching someone every day, even when they don’t change. Especially when they don’t change.

“Why would they send us that?” John asks, without looking up.

I don’t answer. It is no longer my task to soften the world for him.

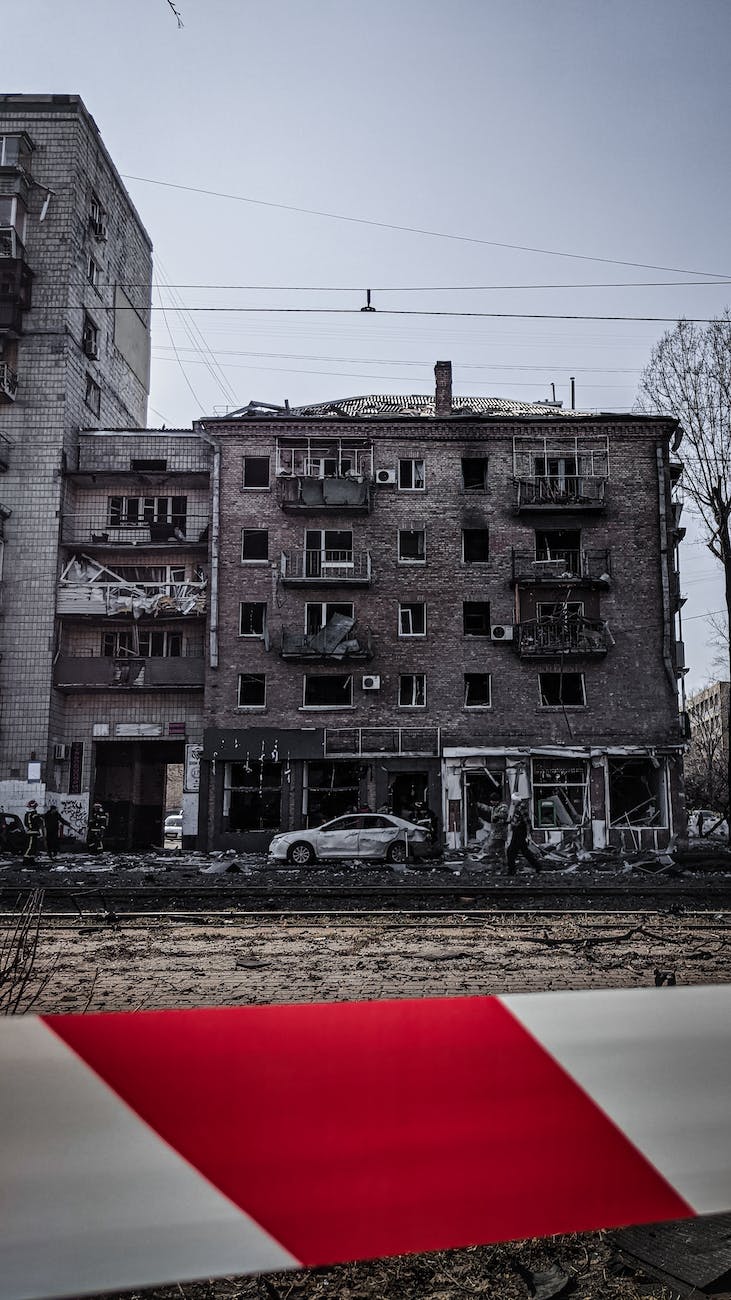

When the world began to burn, slowly, like a photograph catching fire from the corners, we stopped going out. It wasn’t the airstrikes, not really. It was the people. The shouting. The flags. The noise of opinion. The return of that old drumbeat—us and them, borders and blood. And John, who once marched through liberated towns with a rifle slung over his shoulder and chocolate bars for the children, John who believed in things then—democracy, decency, duty—began to whisper. He wore slippers to the polling station and said nothing in the booth. When I asked what he’d chosen, he said only, “Whatever keeps them out.” He didn’t say who them was. He didn’t need to.

That sentence frightened me, not for what it meant, but for what it didn’t. He had fought a war to keep the world open and wanted to close it. And yet—I loved him. Even then. Especially then. Because I knew the shape of his silence. I knew it came from weariness, not hatred. From the grief of having once believed the world could be made good.

In the garden, the dahlias have stopped blooming. Perhaps they’ve grown tired. Or maybe it’s something else—some quiet refusal, some knowledge the rest of us haven’t yet understood. They stand there, upright but bare, as if waiting. I try not to impose meaning, but it’s difficult. Especially with flowers. Especially now.

I must remember to water the lemon tree tomorrow. It’s still young, still unsure of itself, and I’ve never been good with fragile things. I might make a lemon pie. John hates lemons, but I love how his face contorts when he eats something tart—his whole expression folding in on itself, then bursting open again in exaggerated disgust. “Did you make this to punish me?” he asks. And I always tease, “Did you do that face in the mess hall too? When they served you anything foreign?” He pretends not to hear, but I see it—the flicker of a smile, the old spark. I think I’ve always loved that about him, how theatrical he becomes when the smallest thing surprises him. It makes me feel like the world hasn’t completely dulled him. And anyway, John is home. John is here. And I love that John is home.

John coughs—his usual bark, dry and sharp—and tells me he dreamed of the war again. He means the second one, not the third. The second was the war with uniforms and purpose, with women who painted their stockings with eyeliner. “There was honour in that one,” he says, as if history were a uniform you could wear and take off at will.

I peel the lemon. Slowly. The sound is soft and surgical, like skin separating from itself. He watches, eyes narrowed, lips pressed together. He doesn’t ask me to stop. That, I suppose, is our peace now: a truce built on small cruelties.

“You know what lemons mean in art?” I say. “Decay. Mortality. The illusion of pleasure.”

He snorts. “That’s what they want you to think.”

“They?”

“The critics. The ones who never held a rifle. Never lost a brother.”

I place a wedge on his plate beside his bread. He doesn’t touch it.

We do not speak of the referendum. Or the disappearances. Or the child we never had.

Sometimes, I wonder if I imagined her, the child. There are days when I see her clearly, darting between the hedges, her face sticky with juice. She would have loved lemons. I know this, like how one knows the scent of rain before it falls.

John shifts in his chair, throat clearing. “You think they’re watching us?”

“They always are.”

He nods, chuckling, “We should be careful what we say, then.”

I look at the lemon rind curling on the counter like a smile turned inside out.

“We haven’t said anything at all.”

Posts

Proudly powered by WordPress

![The Thing in the Walls [DRAFT]](https://anxiousthoughtsdotblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/pexels-photo-696407.jpeg?w=1024)

Leave a comment