Untranslated

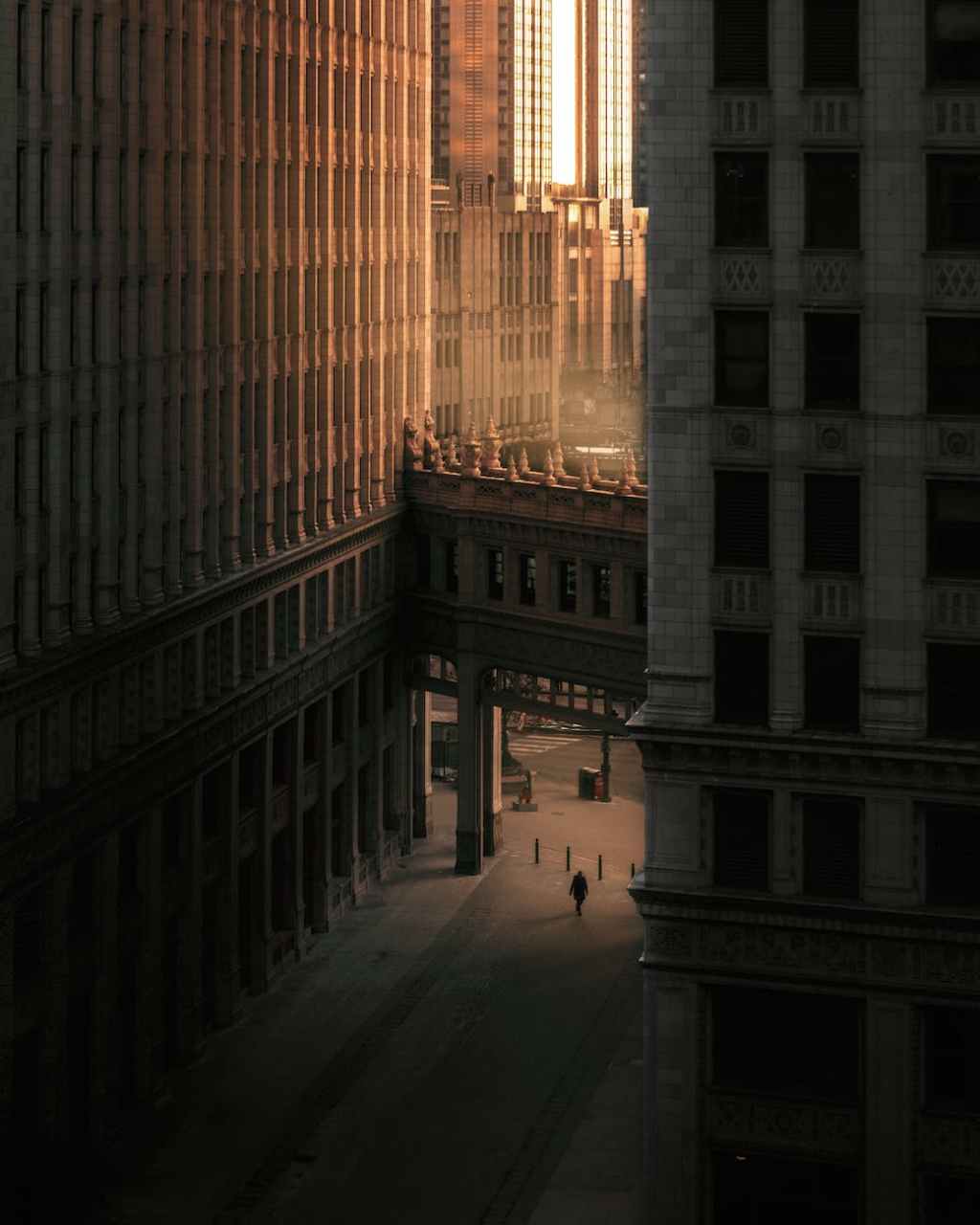

I have always been aware of the weight my name carries.

It is not a common name, at least not in the places I have lived. It is not difficult, either, yet it does not quite belong in every mouth that attempts it. Sometimes, it is clipped too short, severing the fluidity of its vowels. Other times, it is stretched awkwardly, syllables landing in homes they were never meant to. It is an easy name, and yet, somehow, it is always just slightly off when promised by others.

I have heard my name in a thousand different voices, each shaping it into something almost—but not quite—mine. But only one voice spoke it precisely as it was meant to.

Fairuz chirps my name the way it was meant to exist.

Yara, her voice unfurls like silk. Effortless. Soft yet deliberate. A spell, a rustle on the edge of memory. The voice of a Lebanon lingers in my parents’ minds, the voice of mornings still heavy with sleep, the voice of a history I inherited but never lived. My name belongs in these lines. It settles. It does not need to be adjusted, explained, or reshaped for their convenience.

And yet, outside the song, it is something else.

[Names are strange creatures, don’t you think?]

We inherit them before we have the words to shape ourselves, before we understand who we are or who we might become. They cling to us like ghosts, whispering of ancestors we never knew and places we may never set foot in. A thread—sometimes a tether, sometimes a prophecy, sometimes a weight we carry without question.

Have stories always known the magic of names? Achilles, do we not hear the weight of inevitability, bound to both glory and ruin? Is Heathcliff not a storm, howling across the moors, carrying love and vengeance tangled in its wake? Is Jane Eyre a quiet rebellion, insisting on her own selfhood in a world that seeks to erase her? And what of Pip—small and unassuming at first, swelling with the weight of expectation and reinvention?

Jane Austen holds the name Elizabeth as if it were her own child, cradling it between her pages, caring for its cadence. Does Mr. Darcy know the weight his name will carry centuries later, the way it will flutter in the hearts of readers? Would Shakespeare’s Macbeth marvel at the way his name spills across academic papers, a lesson, a legend, a warning? How curious it is to be a writer, to wander through meadows or city streets in search of a name to anchor a story.

I wonder—how did Brontë construct Earnshaw into her desk? How did Beowulf first thunder into being? How many names have been spoken into existence, only to be forgotten? And how many still wait, lumping the tongues of those who have yet to speak them?

[My name has been an exercise in translation]

The exhaustion, hearing your name mispronounced over and over again. It’s a quiet thing, a minor inconvenience in the grand scheme of the world, but it persists. The subtle pause before someone attempts it, the way they shape their mouth hesitantly, the way they sometimes ask, Am I saying it right? And I, tired of explaining, tell them, Close enough.

But what is close enough when it comes to a name? What does it mean to hear a version of yourself that is just slightly distorted—like a vowel stretched too thin, a consonant eased into something unrecognizable, a syllable left behind?

Does Gregor Samsa wake up as Gregor in every language, or does his metamorphosis begin with the way his name bends to fit a new alphabet? When we say Odysseus, are we summoning the same man the Romans called Ulysses, or has the ‘d‘ softened into an ‘i‘, the shape of his journey altering with each phonetic shift? Does Don Quixote hear himself in every translation, or does his name crack and reform, its fricatives sanded down, its rhythm restructured?

And what of those whose names are clipped, stretched, or reassembled for the ease of foreign tongues? When Sayyid becomes Sid, when Wei-Wei is rounded into Vivi, when a glottal stop is smoothed over like an inconvenience—what is lost in the remaking? When the delicate trill of an ‘r’ is flattened, when a hard ‘k’ is swallowed, does the name remain intact, or does it slip just out of reach?

A name is not merely meaning—it is breath molded into rhythm, a fugitive sound moving through time. It is the hush of a mother’s voice, pooling in the quiet before sleep, the way it unfurls with devotion, the way it curdles in the mouth of a stranger. A name is a contour, a vessel of memory, a spell cast each time it is uttered. But what happens when it is bent, dulled, disfigured? Does it fracture into something unrecognizable, or does it haunt the spaces between mispronunciations, clinging to its former self like an echo just out of reach?

Is language ever truly neutral? To speak a name as it was meant to be spoken—is that an act of restoration? An invocation of the muse? And yet, how often do names endure violence at the hands of convenience, stripped of their inflections, their syllables pruned to fit the limitations of another tongue? How many names have been swallowed whole by translation, hollowed out for ease, softened until they are palatable, hardened until they are foreign to their own histories?

Perhaps a name is not only its shape but its resistance—the way it frays yet refuses to unravel, the way it prances in its distortions, refusing erasure. And what of the names who refuse to be swallowed-Ghassan, Leila, Naji, Handala.

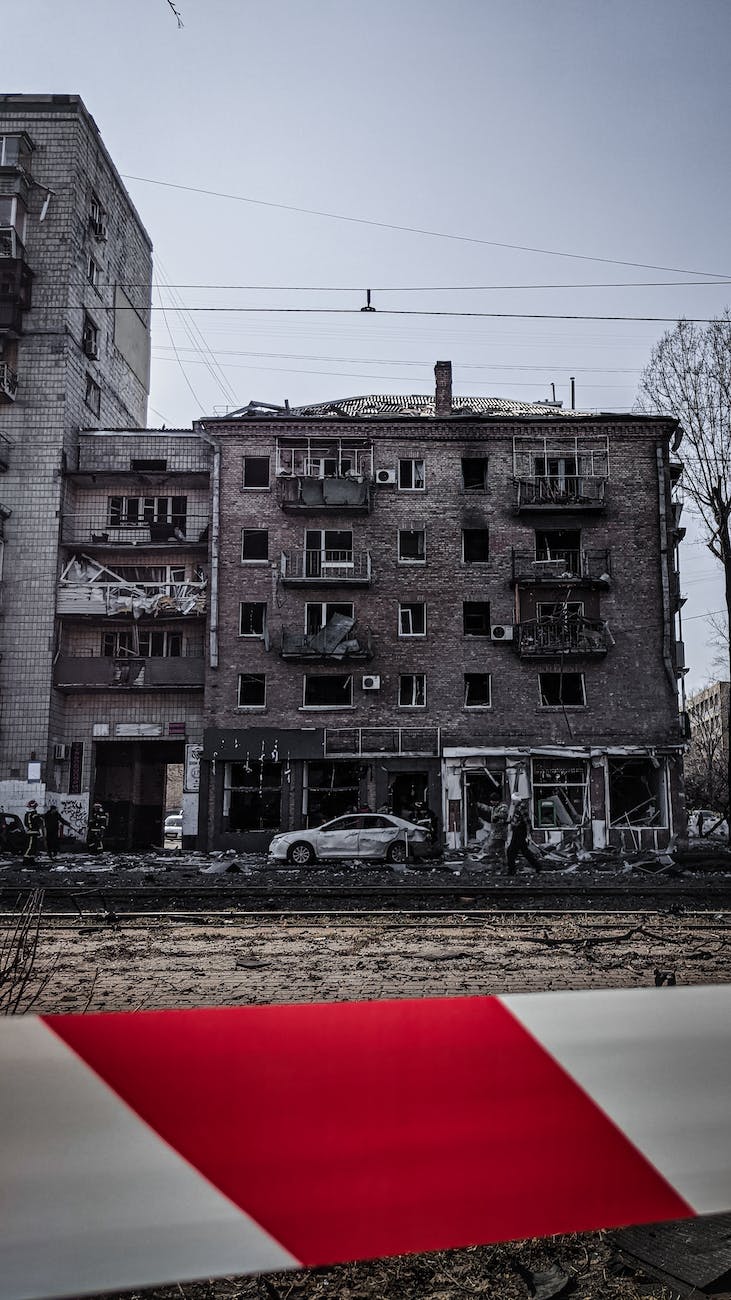

What does it mean for a name to become a banner, a rebellion, a salute, a war cry? When a name is inscribed on a wall, painted across the ruins of a home, etched into the stones of a razed village, does it become something more than a name? When it is chanted in the streets, scrawled on prison walls, or turned into a symbol that outlives its bearer, does it slip the boundaries of identity and become a resistance in itself?

Ghassan Kanafani—how does a name survive exile? Does it carry the weight of every story untold, every return denied? When his name is spoken, does it summon the scent of ink and revolution, the sound of paper igniting under censorship’s hand?

Leila Khaled—how does a name become legend? Does it sharpen into defiance, into an image held in the mind of the world, reprinted and reinterpreted until it is both myth and reality? When history tries to rewrite her, who holds onto her name as it was, unyielding?

Naji al-Ali—when a name sketches a people’s suffering, when it carries their grief, their laughter, their dignity in every inked line, can it ever fade? If Handala stands with his back turned, eternal, does that mean his name will never belong to history but always to the unfinished present?

And the names of villages—Deir Yassin, Lifta, Tantura—are they names, or are they elegies? What happens when a name is all that remains, when the land it once belonged to has been paved over, renamed, redrawn? Do these names still belong to the maps that have erased them, or do they exist now only in the voices of those who refuse to let them be forgotten?

What is a name if not memory shaped into sound? And if memory is resistance, then perhaps the truest form of defiance is simply to keep saying the names.

So, I think of my grandmother, Fatmeh, and how her name became something else on official papers, appealing bureaucratic tongues. I think of family members whose names have been clipped, misspelled, or deliberately edited in immigration offices, classrooms, and workplaces—as if their original forms were too much. Too foreign, too difficult, too unwieldy for the jaws that refused to learn them.

And I think of my own family name: A J E E B.

How my father’s papers spell it Ajib. Just one letter’s difference—a single vowel shift—but does it change the way it sits in the mouth? Does the i in Ajib stand taller, more rigid, while the ee in Ajeeb stretches out like an open palm? One is quick and clipped, the other softer, almost indulgent. But which is correct? Which is the real name, and which is the translation? Or is each simply a version of itself, altered by a moment, a hand, an assumption made at a desk somewhere?

Does it matter?

How would you translate it? Untranslate it?

Would you smooth out the vowels, sharpen the consonants, strip away the sound that oversteps? Would you press it into a shape that fits more easily in your mouth? Or would you let it unravel, let it return to what it was before it was bent, before it was altered by a slip of the pen, a moment of hesitation, a bureaucrat’s impatience?

What happens when a name is rewritten, respelled, re-formed? Does it remain itself, or does it become something else—close, but not quite?

I wonder if my name carries a different fate than my father’s. If Ajib and Ajeeb are, in some unseen way, not quite the same. If a single vowel—one small stroke of a pen—shifts the weight of history, the meaning of belonging. Or if, like so many names before it, it is simply another reminder that identity is always at the mercy of the ones who choose how to write it down.

I no longer correct people as much as I once did. I have accepted that most will not say it as Fairuz does, that there is a version of me that exists in the mouths of others that I will never entirely recognize. But there is power in knowing that my real name resides untouched in my voice, in the voices of my family, in the melody of an old song that plays in the background of my childhood.

That may be enough, right?

Yet, I wonder…

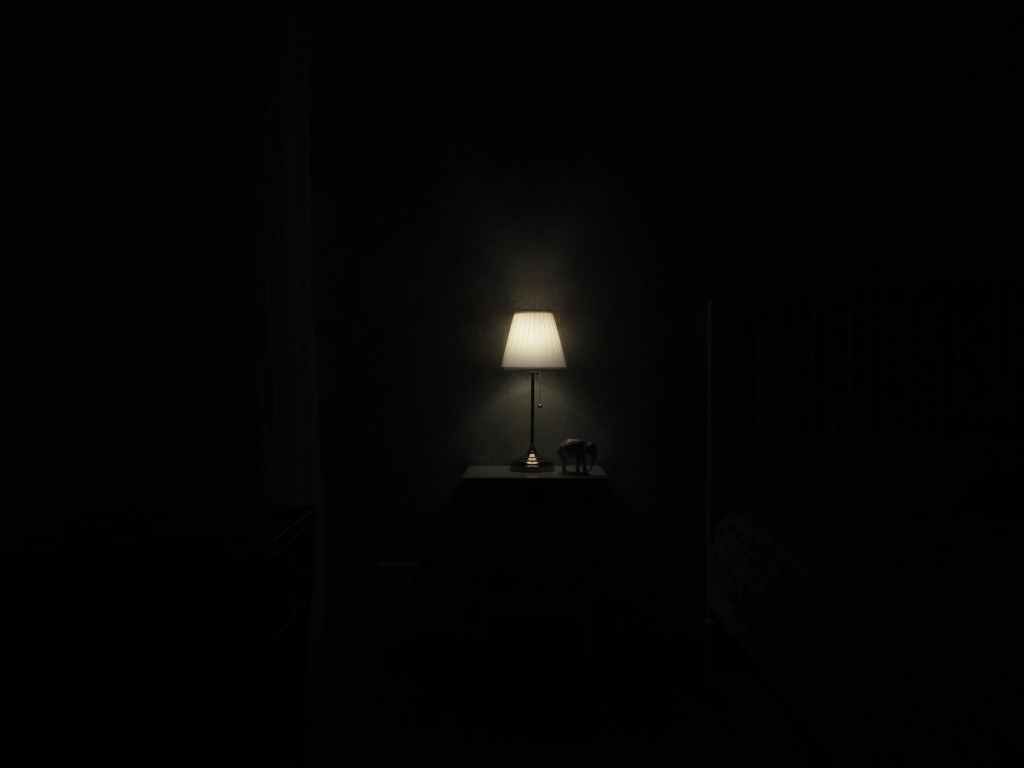

How do you describe a name? How do you hold it? Do you fold it neatly into the drawer of your nightstand before slipping into slumber, or does it hover just above you—weightless, restless, waiting to be spoken?

Does a name die with us?

My name is ____.

But why?

Where and how?

Where do these letters begin, and where do they end? Are they boundaries or bridges? Do they erase themselves in memory, condemning forgetfulness? Or does it protest, an unfinished sentence, a story waiting to be reclaimed?

Resist complete translation?

Slip between idioms, adapting, surviving, changing just enough?

Unscramble, unlearn—unborn, reborn? Unanchored, untamed, untranslated?

![The Thing in the Walls [DRAFT]](https://anxiousthoughtsdotblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/pexels-photo-696407.jpeg?w=1024)

Leave a comment